Although most tattoo detractors are quick to dismiss this art form as a popular fad from modern times, the history of tattoos has evolved over many millennia.

Tattooing is well known to take different meanings depending on the particular culture or geographical region it develops in.

Whether it be a signal of social status, patriotism, personal identity, or even treatment with medicinal purposes, one thing is for sure: the long-lasting evolution of tattooing through time is certainly a wild ride.

Ötzi: The Tattooed Iceman

In September 1991, a couple of German tourists were hiking up the Italian side of the Ötzal Alps. As they made their way into the mountain, they came across frozen human remains which they thought belonged to a recently deceased mountaineer.

The real identity was that of a hunter who had been dead for 5,300 years. The iceman, later dubbed as Ötzi, was so remarkably well preserved that scientists were able to tell many things about his last days.

Ötzi is thought to have been tattooed using a method that punctured the top layer of the skin. Shortly afterwards, the wound would be rubbed in with charcoal.

The minimalist designs scattered across his body consisted of different groups of straight lines. These tattoos have long been hypothesized to have medicinal purposes.

Ötzi suffered from lower back pain and degenerative joint disease of his knees, hips, and wrists. The strategically placed tattoos functioned as an early form of acupuncture by stimulating the nerves underneath the skin.

The Tattooed Army from Ancient Britain

When the Roman Empire sought to invade Britain in 55 BCE (Before Common Era), they encountered the fierce resistance of the Picts, a warrior race that displayed impressive art on their bodies.

No human remains nor written records exist to account for the history of the group of tribes which inhabited modern northern Scotland. What little is known comes from Roman literature.

So much did their body art come to be synonymous with their culture, that some knew them as the Pretani, a Celtic word that meant “painted” or “tattooed”.

Perhaps the most famous account of the Pict came from Julius Cesar. When reflecting upon the Gallic Wars, the famed dictator wrote, “All the Britons dye themselves with woad, which produces a blue color, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible”.

Tahiti, Tatau, and the Origin of the Word Tattoo

Ever wondered where the actual word “tattoo” comes from? Surprisingly, the English term finds its roots in Tahiti, French Polynesia.

When British explorer, Captain James Cook set foot on the island in 1769, he recorded the existence of a practice named “tatau” by the locals. The name, inspired by the sound tattooing produced (tat tat) was widespread across the island.

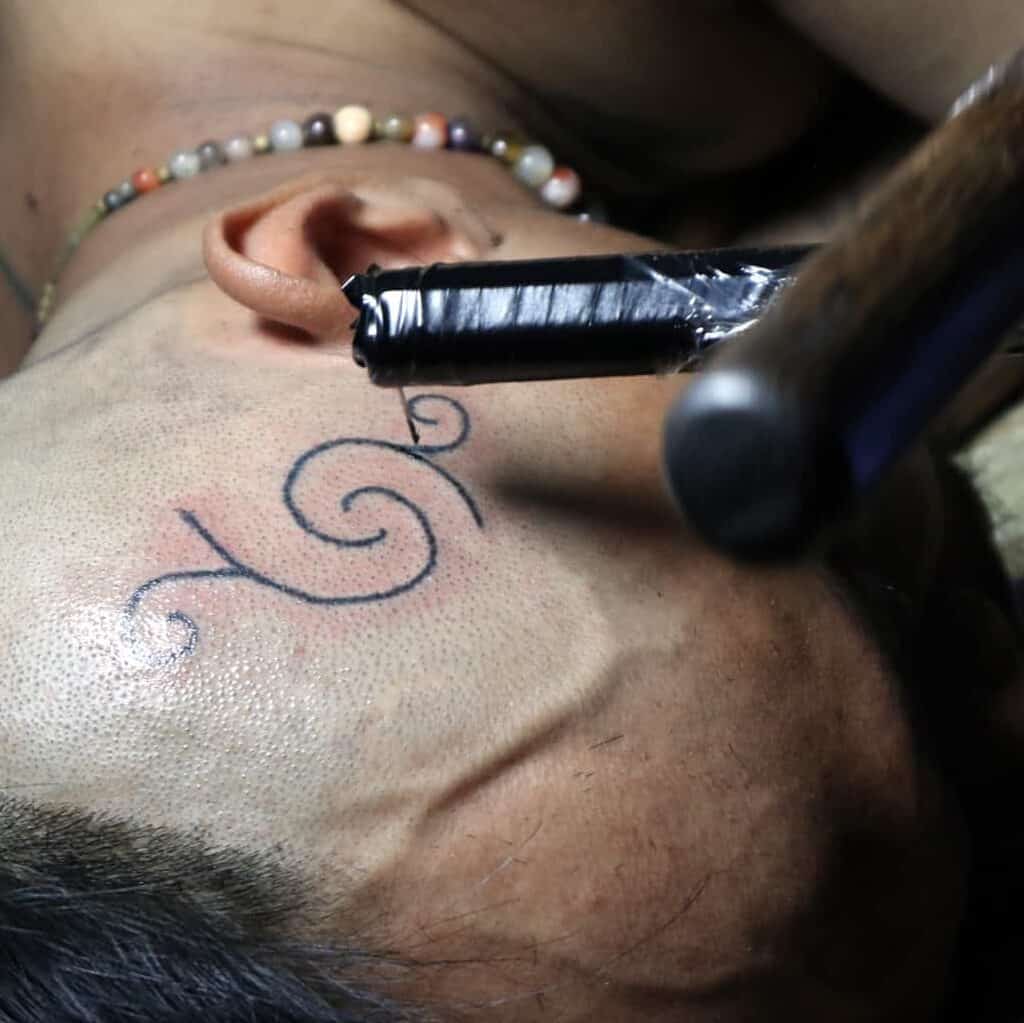

A tool locally known as tatatau is used to achieve this traditional tattoo style. With the tatatau, tattoo artists tap away at a long comb-like stick with needles using a mallet.

James Samuela, a contemporary Polynesian tattoo artist, has noted:

“The tools are made specifically for you, used only on you. It takes two artists to do a traditional tattoo — one to stretch the skin and the other to do the tat-tau-ing”.

Tahitians have been trained as tattoo masters since ancient times.

Regarding their meaning, a traditional Polynesian tattoo is meant to display essential information about the wearer such as their rank within their community, their past, or their genealogy.

Tattoos were also a materialization of a person’s “mana,” that is, their spiritual prowess. The process of getting tattooed itself was believed to be a way to achieve power.

Thematically, all symbols in Tahitian tattoos reference the basic elements of the ocean, earth, wind, and fire. It is also important to note that each Polynesian island perfected a particular tattooing style.

Nevertheless, this practice decreased in popularity after being banned by the Tahiti-based French Ministry of Health in 1986. The government pointed out the difficulty in sterilizing the wooden and bone equipment as justification for the ban.

These prohibitions stayed in place until 2001. Unfortunately, there are only a handful of artists left in Tahiti who still practice this traditional art form.

Ta Moko: a Sacred Statement Turned into Horrendous Trade

Not far from French Polynesia, the Māori people from New Zealand also saw tattooing as a practice of religious and spiritual significance. Face tattoos, known as Ta Moko, told of the family history, level of wisdom, as well as the social standing of the wearer.

Rather than puncturing the skin with needles, Ta Moko were created by scarring the skin. At the turn of the 19th century, European missionaries arrived in New Zealand intending to convert the natives to Christianity.

As part of their public agenda, a Māori chief known as Hongi sailed back to England with a group of missionaries in 1814.

After a productive visit where he collaborated with Oxford scholars to translate the Bible into Māori, as well as a successful audience with King George IV, Hongi received many expensive gifts.

Later on, during his trip back home, he traded said presents for weapons and ammunition. The admiration toward Māori body art would soon prove to be deadly.

Having armed his tribe, Hongi raided nearby villages. Other tribes sought out to follow his example by establishing trade with European nations.

Well aware that the tattooed shrunken heads of the deceased, known as mokomokai, were seen as a luxurious commodity by the Europeans, The Māori started exchanging the heads of their enemies for weapons.

Once they ran out of traditionally produced shrunken heads, they started fabricating imitations with the heads of enemies they’d taken as prisoners. In the ensuing years, the horrendous trade would result in a dramatic decrease of the Māori population.

Africa as the Land of Scarification

On the African continent, evidence of tattooing has been traced back to Egyptian mummies. The three-thousand-year-old mummy of Amunet, a priestess, is thought to be the oldest among them.

Curiously enough, there hasn’t been any male tattooed mummies found from ancient Egypt. However, in other regions of Africa, several tattooed male mummies have been located. Their designs serve as an allusion to the deities of the sun.

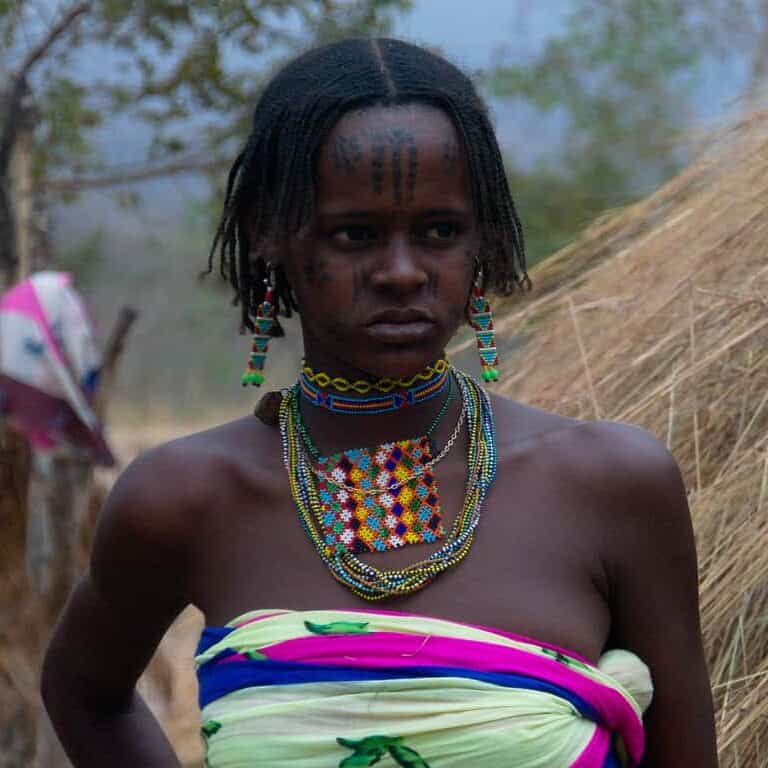

In Africa, the tattooing method of choice is scarification. Scarification is practiced by incising the skin with sharp instruments such as knives, glass, stone, or coconut shells in a way that controls the appearance of the process of scaring.

Afterwards, dark pigments and ash are sometimes rubbed on wounds to accentuate the designs.

Culturally perceived as a symbol of beauty, scarification has long been used to mark a woman’s transition into puberty and later marriage age. When pregnant, women also receive markings on their backs as an omen of good luck.

As a widespread practice, these markings were the equivalent of a greeting card in ancient times. They made a clear statement regarding a person’s rank in society, their family, clan, and tribe.

Not only was the product of scarification thought to keep evil spirits away, the markings were also used to avoid attacks among fellow comrades whenever nearing tribes fought each other.

Nevertheless, concerns about the transmission of HIV increasingly halted the practice over the past decades. Nowadays, thought to be a dying art only practiced in rural areas, tribes like the Fulani are still proficient in scarification.

From a young age, children are marked in their cheeks to ward off evil spirits. This process, painful to say the least, is also seen as a rite of passage that helps children understand the cold nature of life: how every person arrives to the world to suffer.

Between Tradition and Stigma: The Japanese Situation

In Japan, tattooing is thought to have originated during the Jomon Period (10,000 BCE-300 CE). In the third century, Chinese historians would write of the existence of Japanese men with bodies and faces decorated with designs of fish and shells.

However, tattoos were not only a representation of a person’s lifestyle, they were also a severe form of punishment that branded a person for life. This duality in the societal meaning of Japanese tattooing would remain true for centuries to come.

Just like with the Polynesians, tattooing styles also varied between Japanese tribes. Perhaps the most recognizable among them were the Ainu, who tattooed their faces with large smiles.

The Ainu saw tattoos as rites of passage. Their designs were also a telling sign of an individual’s prominence within their community.

During the Edo Period (1603-1868), tattooing was proclaimed illegal on the grounds that it was “deleterious to public morals”. Ironically, tattoo artists were still allowed to work on foreigners who started arriving from overseas in search of their designs.

This was also the period that saw the rise in popularity of tattooing among the feared Yakuza (gangs).

By 1868, Japan had opened its doors to international trade for the first time in centuries. They had attempted to do so centuries before, but limited their trade to the Chinese and the Dutch after becoming wary of the connection of the West to Christianity.

While the Japanese quickly became internationally renowned for their luxurious fabrics, another export would soon catch the attention of the public: their traditional tattoos.

The War and Tattoos as a Display of Patriotism

Although tattoos were already popular with sailors, around 90% of them had gone down the needle by the time the 1940s came along; many soldiers also took to the needle to display their patriotism during the war. The navy servicemen were some of the first to welcome tattoos during their long voyages.

Even though popular designs served as homages to places they had visited, army officials also decorated their bodies with the names of their loved ones.

Once World War II broke out, and the United States joined the conflict, the Hotel Street district in Hawaii became a popular gathering place for the military. The area served as the backdrop for a booming business where tattoo artists set up shop during the daytime.

In its heyday, the area attracted many soldiers looking to get tattooed. Anywhere from 300 to 500 tattoos were made in the Hotel Street district on any given day.

Among tattoo artists, Sailor Jerry soon gained notoriety as one of the scene’s most celebrated figures with his portfolio of colorful and patriotic designs. The artist is also known for developing innovative techniques that allowed ink to settle better on skin.